This Sunday 22 May, Pauline Jaricot will be beatified by the Church. This year we are also celebrating the bicentenary of her work to help Catholic missionaries throughout the world.

On 3 May 1822, in Lyon, the Society for the Propagation of the Faith – which still exists within the Pontifical Mission Societies – was officially born. It was primarily to help the MEP missionaries and their missions in China that Pauline Jaricot devised an ingenious fundraising system. This anniversary gives us the opportunity to shed light on the links between Pauline and the MEP at the beginning of the 19th century and to see how the missions in Asia were the first beneficiaries of this young girl’s missionary intuition.

From London to Lyon, the idea of the “penny a week”

At the end of the 18th century, the Foreign Missions Society was in the most difficult situation of its history. The directors of the Seminary were exiled, and all possibilities of recruitment and maritime links to Asia were cut off for almost 10 years. Supporting the 48 fathers who were still there, whether by financial or human resources, became an almost impossible task. The MEP no longer had a legal existence, had lost all sources of income and no longer even owned their buildings on the rue du Bac.

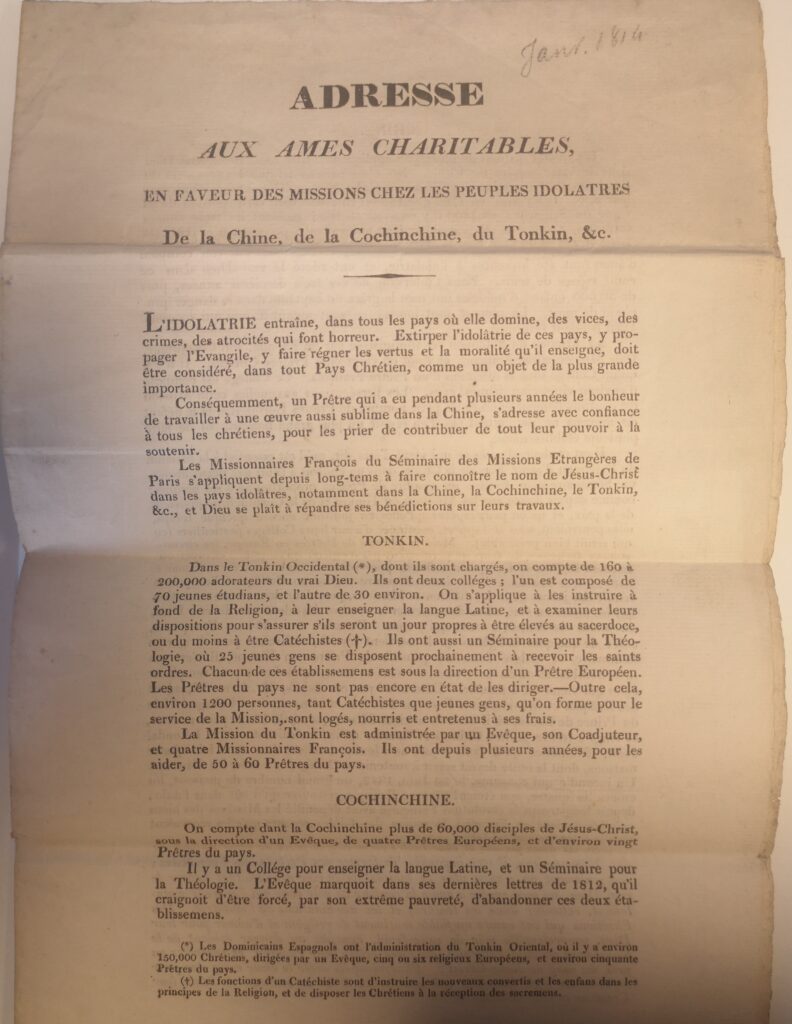

Fr Denis Chaumont, former director exiled in London, tried to raise funds from English Catholics and French emigrant networks. He took advantage of his presence across the Channel to get some ideas from Protestant missionary institutions. On 31 January 1794, while the Terror was in full swing in France, he published an Address to Charitable Souls in London in favour of the Missions to the idolatrous peoples of China, Cochinchina, Tonkin, etc., in which he proposed that any person of good will make a donation according to his or her means, however small. His words were inspired by a sentence read in an Anabaptist temple: “The world is made up of atoms and the sea of drops of water: thus the smallest contributions together will produce a sum that will provide the means to spread the Gospel.”

P. Denis Chaumont, Adresse aux âmes charitables en faveur des Missions, London, 1794

Back in Paris in 1814, Fr Chaumont took advantage of the security granted to religious institutions by the Restoration to further structure these small fundraising efforts. Relying on the parish network of the French dioceses, he counted on the goodwill of lay people and priests to found associations called “auxiliary societies”, whose members would commit themselves to reciting the prayer of St. Francis Xavier and the Remembrance for the missions every day and, if they could, to supporting them financially. The statutes of these associations state that “all classes of citizens, even the poor, by setting aside a penny or two each week for this purpose, have the satisfaction of contributing to the progress of the Gospel”.

This is how the idea of the “penny a week” was launched, which was also the organisational basis of the Work of the Propagation of the Faith. In 1817, this MEP association of “prayer for the propagation of the faith” was officially recognised by the Holy See, which granted its collaborators special indulgences. In 1818, it was already raising funds throughout France and even in Mauritius.

Pauline and Philéas Jaricot invested in the missions in China

At the same time, in Lyon, a young girl from the rich bourgeoisie sought with all her heart to make Christ known in her surroundings as well as at the ends of the earth. In 1817, Pauline Jaricot, who, according to her, had just experienced a lightning conversion of heart, founded the Réparatrices du cœur de Jésus méconnu et méprisé, an informal association of pious and devoted women who contributed to the missionary work with their obols and prayers. Pauline was particularly sensitive to the cause of the missions in Asia, firstly because she had undoubtedly heard of the MEP prayer association, and secondly through the intermediary of her beloved brother, Philéas, who had entered the seminary of Saint-Sulpice in 1820 with a view to being a missionary in China. In Paris, Philéas often went to rue du Bac where one of his friends from Lyon, Jean-Louis Taberd, was preparing to leave for India. Philéas tells Pauline about the efforts made by the MEP to collect the money necessary for the missionary’s trousseau and journey. He also told her that “with 150 francs a year, one could feed a catechist in China, and that each catechist could baptise up to 2,500 children [1]“.

Pauline had the intuition that, in order to grow, the movement of generosity in favour of the MEPs needed to be better organised. In one evening, she came up with the ingenious system of collecting pennies by the dozen: each week, ten donors, organised among themselves, hand over their respective pennies to their leader of the dozen, who then passes them on to the leader of his or her centurie, who then passes them on himself, etc. This was a light and efficient structure that gave the idea of a penny a week a boost. The system took off in Catholic circles in Lyon and, in 1819, Pauline had 1439.35 livres sent to rue du Bac. In 1821, the accounts of the Seminary of Paris record several donations made by Abbé Philéas Jaricot. In 1820, the association already had a thousand members and took on the name “Propagation of the Faith” that Denis Chaumont had given to the MEP.

Always fond of the stories from Asia transmitted via Philéas, Pauline was aware that a donor who was kept informed of the life of the missions would be even more inclined to prayer and generosity. She therefore distributed copies of the Nouvelles lettres édifiantes des missions de la Chine et des Indes orientales (“New Edifying Letters from the Missions of China and the East Indies”), which the Paris Seminary had printed from the letters received from the MEP fathers. Pauline now had the three pillars of the Work in place: prayer, almsgiving and the press.

Pauline Marie Jaricot

Serving the universal Church

Naturally, in this France of the Restoration where vocations and the missionary call were reborn, other initiatives and Catholic institutes were created in favour of evangelisation. On 3 May 1822, Benoit Coste, a friend of Philéas, brought together various actors to define their vocation: why limit themselves to the missions of Asia? Shouldn’t we be open to the universal Church? But then, how to achieve such a scope? Pauline was not invited, but her friend Victor Girodon spoke on her behalf:

“When I explained the way in which we do the work of the Propagation of the Faith, its name, its penny per week, its centuries, its divisions and even its revenue tables and the reading of the news from the missions, no one asked for any other initiative. They simply adopted the plan and the proposed organisation [2].”

Thus, Pauline’s work, born for the MEP, became, following this founding meeting, the Work of the Propagation of the Faith, managed from Paris and Lyon for the whole world. Out of modesty and spiritual height, Pauline withdrew from the frameworks; a few decades later, it will have been forgotten that she was the source of it.

Approved by the Pope in 1823, the Work continued to grow in leaps and bounds. It raised about 250,000 francs a year until 1833, when it finally passed the million mark. By 1840, it was already widely spread internationally.

The MEP’s printed material had given way to a real review, the Bulletin des Annales de la Propagation de la Foi, which published 10,000 copies from 1825 onwards. Even though they no longer had exclusive rights, the MEP drew a good part of their income from the funds raised by the OPF, and therefore published in the Annales de la Propagation what the missionaries had written in Paris. Through annual reports, the directors of the MEP informed the central council of the OPF of the destination of the donations. In 1835, for example, they explained that the Society now had 72 members and 150 indigenous priests, which represented 100,000 francs of viaticum to be provided, and that they were in great need of money for the brand new mission in Korea and to build the brand new seminary in Penang, Malaysia [3]. Throughout the 19th century, the MEP never lacked the annual endowments of the Work. After its incorporation into the Pontifical Mission Societies in 1923, its activities continued on the same scale.

Allocations paid by the OPF to the MEP for the year 1929

In his Histoire générale de la Société des Missions Étrangères, Fr. Adrien Launay summarises this very fruitful marriage of several missionary intuitions:

“Thus, most of the time, works are founded by the successive contribution of several wills and several intelligences. Their birth is difficult and slow, until the day when a ray of providential grace passes over them and causes them to flourish and bear fruit [4].”

[1] Quoted by Catherine Masson, p. 157.

[2] Quoted by Catherine Masson, p. 142.

[3] Letter “To the members of the two central councils of the work of the propagation of the faith”, AMEP 5392.

[4] Vol. II, Paris, Téqui, 1894, p. 512.