The leprosarium of Pondicherry

Discover the functioning of the leprosarium of Pondicherry, through archives resulting from the digitization of our India collection.

Status of the project :

In 2021, the IRFA invited Mrs Marianne de Bovis, a curator-restorer specialised in paper, to take part in a training course designed to accompany the operators in charge of the digitization of 17th-19th century archival registers concerning the missions in India. A methodology detailing the procedure to follow in handling these archives, about a third of which are in a critical state of deterioration, was put in place following this training.

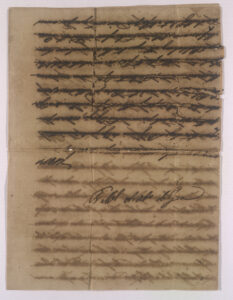

These archives contain iron gall inks which, under the effect of humidity, cause mechanical stress on the documents. This stress, aggravated by human handling, leads to corrosion of the ink, which eventually renders the document completely unreadable.

Example of corrosion iron gall inks

The example of the leprosarium of Pondicherry through a list of expenses, reports, memoirs and letters (1859-1887):

The leprosarium was created by order the 6 September 1842, thanks to a donation of the Count of Richemont, former Governor General of Pondicherry and founder of the Royal College, where the Paris Foreign Missions (MEP) provided teaching from 1836 to 1899. Initially placed under the control of a Benevolent Committee, it was entrusted to the Society of Saint Vincent de Paul in 1858, with the approval of the Minister of the Navy and the Colonies. As the Society had no legal existence in India at that time, the management was handed over to the MEP at the request of the founder until 1870, when the Paris Foreign Missions took over the complete running of the leprosarium.

On 1 May 1880, following an inspection and an order prohibiting the circulation of lepers on the public highway, the local administration decided to bring the leprosarium back under the authority of the Benevolent Committee. This decision was contested and rose a series of arguments which shed light on the organisation of the leprosarium as well as on the relationship between the missionaries and the Colonial Office, in the context of the secularisation laws.

The organisation of the leprosarium :

“The last general inspection had noted (in 1878) the deplorable situation into which the leprosarium had fallen.” Viscount de Richemont’s letter to the mayor of Pondicherry of 14 May 1880, repeating the order of 1 May.

This is what contains the note given by the Colonial Office to Viscount Desbassyns de Richemont, Senator of India from 1876 to 1882 and son of the founder of the leprosarium. This note is the subject of a reply which aims to prove the good management of the leprosarium under the direction of the MEP.

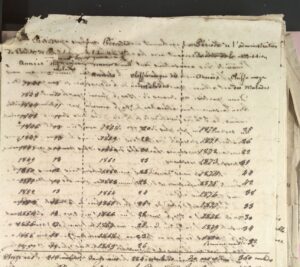

It details the situation of the leprosarium between 1870 and 1880, showing an overall lack of resources for an ever-increasing number of patients. Thus, the total income from relief and allowances provided by the Benevolent Committee and the local administration amounted to about 2,227 francs for one year. To this must be added a variable income from the coconut plantations, as well as various donations and alms.

The staff of the leprosarium was mainly composed of one man who, from 1854 onwards, fulfilled the triple function of keeper, catechist and accountant. He also looked after the patients, while a woman was in charge of external purchases. If we subtract the caretaker’s salary of 200 francs and allow 10 francs per month for the care of each patient, it is possible to take care of 17 to 18 lepers per year at the most.

Table showing the number of patients under the various administrations: 213 for the Comité de bienfaisance over 16 years, 284 for the St Vincent de Paul Society over 12 years and 360 patients for the MEP over 10 and a half years.

This quota was largely exceeded when the MEP had to ensure the running of the leprosarium in 1870. The arrival in 1874 and 1875 of boats loaded with lepers from Reunion Island, which the administration sent to the leprosarium in Pondicherry without “any compensation” (Answer to the note from the Colonial Office, 2 August 1880), doubled the number of patients at once. From then on, between 1842 and 1880, the average number of patients increased from 8 to 32.

The “affair”:

This question of the management of the leprosarium takes a certain extent and leads Viscount de Richemont to write to the Minister of the Navy and the Colonies, Jean Bernard Jauréguiberry (1815-1887), as well as to Léon Guerre (1834-1895), the first elected mayor of Pondicherry.

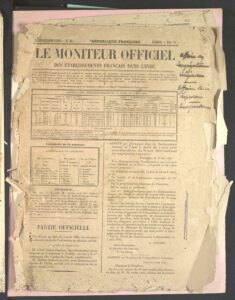

Tribune of the Moniteur Officiel of 7 May 1880 containing the new internal regulations of the leprosarium

The Viscount de Richemont explained in particular that the Benevolent Committee did not own the leprosarium, which had been set up with his father’s funds and those of the colony, and that the decision to entrust its management to the MEPs was not temporary but had “a definitive character” (undated letter from the Viscount de Richemont to the Minister of the Navy and the Colonies). He also maintained that the situation of the leprosarium had not deteriorated since the MEP were in charge, but did not demand a return to the previous situation, as he was “not a political friend of the men who are currently in power” (Letter from Viscount de Richemont to the Mayor of Pondicherry dated 14 May 1880, repeating the order of 1 May). However, he asked that the chaplain remain chosen from among the members of the MEP and be part of the board of directors.

In fact, the inspection report mentions a missionary who was both chaplain and director of the leprosarium and a teacher at the colonial college, and who was then presented as being unfit to fulfil his duties. This was Fr Désirée Bordereau, who had joined the Pondicherry mission in 1851. Using alms and his own savings, he built a chapel for the leprosarium, which became the centre of a pilgrimage to Saint Lazarus. He devoted 15 years of his life to the care of the sick and earned the nickname “Father of the Lepers”, before being removed from the leprosarium in 1880.

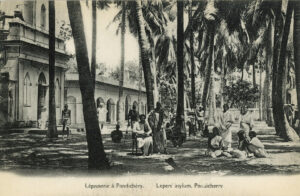

Chapel of the leprosarium, built by Fr Désirée Bordereau

A new regulation was then established by the Benevolent Committee: the budget was doubled and the staff reinforced. However, this did not compensate for the poor management of the leprosarium, which was finally entrusted to the Sisters of Saint Joseph of Cluny from 1898 until 1904, when they were expelled from the buildings, which had become entirely secular.

Sister of St Joseph of Cluny with a group of lepers